Why Its So Hard to Tell Which Climate Policies Work

Why its so hard to tell which climate policies actually work – Why it’s so hard to tell which climate policies actually work? It’s a question that keeps climate scientists, policymakers, and concerned citizens up at night. The truth is, figuring out what works and what doesn’t is incredibly complex. We’re dealing with a system – Earth’s climate – that’s incredibly intricate, constantly shifting, and prone to surprising feedback loops.

Add to that the challenges of gathering reliable data, the influence of socioeconomic factors, and the messy realities of political maneuvering, and you’ve got a recipe for uncertainty.

This isn’t to say we shouldn’t try to find effective solutions. Far from it! But understanding the inherent difficulties involved is crucial if we want to approach climate action realistically and effectively. Let’s delve into the complexities, explore the challenges, and see if we can shed some light on this crucial issue.

The Complexity of Climate Systems

Predicting the effectiveness of climate policies is a monumental challenge, largely due to the inherent complexity of the Earth’s climate system. It’s not simply a matter of reducing emissions and observing a linear decrease in global temperatures. The climate is a dynamic, interconnected web of processes, making it incredibly difficult to isolate the effects of any single intervention.

Unpredictability and Non-linear Responses

The climate system exhibits significant unpredictability due to its chaotic nature. Small changes in initial conditions can lead to vastly different outcomes over time, a phenomenon known as the “butterfly effect.” This inherent variability makes it challenging to confidently predict the precise impact of even well-designed policies. For example, a policy aimed at reducing deforestation might have a positive effect in one region, but unintended consequences, such as altered rainfall patterns, in another.

The system’s response is rarely linear; a doubling of emissions doesn’t necessarily lead to a doubling of warming. Thresholds and tipping points exist, where relatively small changes can trigger abrupt and potentially irreversible shifts in the climate system, such as the melting of major ice sheets.

Feedback Loops and Amplification Effects

The climate system is riddled with feedback loops, both positive and negative, which further complicate matters. Positive feedback loops amplify the initial effect of a change, while negative feedback loops dampen it. For instance, the melting of Arctic sea ice reduces the Earth’s albedo (reflectivity), leading to increased absorption of solar radiation and further warming – a positive feedback loop.

Predicting the net effect of these interacting feedback loops is extremely difficult, requiring sophisticated climate models that are still under development. The interactions between clouds, aerosols, and ocean currents are particularly challenging to model accurately.

Unforeseen Consequences of Climate Policies

History is replete with examples of unforeseen consequences arising from environmental interventions. The introduction of CFCs, initially hailed as miracle chemicals, ultimately led to the depletion of the ozone layer, highlighting the potential for unintended and far-reaching effects. Similarly, biofuel policies, intended to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, have in some cases led to deforestation and biodiversity loss, negating some of their intended environmental benefits.

These examples underscore the importance of careful consideration of potential unintended consequences when designing and implementing climate policies.

Limitations of Climate Models in Predicting Policy Effectiveness

Different climate models utilize varying levels of complexity and data inputs, leading to differences in their projections. The accuracy of these projections is limited by our understanding of the climate system, computational constraints, and the availability of reliable data.

Figuring out what actually works in climate policy is a nightmare; so many variables! It’s like trying to untangle a conspiracy, and speaking of conspiracies, the recently unsealed Epstein docs exposed allegations against rich and powerful figures, highlighting how difficult it is to uncover the truth behind powerful interests. This reminds me of how hard it is to see the real impact of climate policies when big money is involved, obscuring the effectiveness of different approaches.

| Climate Model | Spatial Resolution | Process Representation | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCM (Global Climate Model) | Coarse (hundreds of kilometers) | Simplified representation of many processes | Limited accuracy at regional scales; uncertainties in feedback processes |

| RCM (Regional Climate Model) | Finer (tens of kilometers) | More detailed representation of some processes | Requires boundary conditions from GCMs; still significant uncertainties |

| Earth System Models (ESMs) | Varying | Includes biogeochemical cycles and other Earth system components | Computationally intensive; still developing understanding of interactions |

| Statistical Models | Varying | Relatively simple statistical relationships | Limited ability to capture complex dynamics and non-linear responses |

Data Challenges and Measurement Issues

Evaluating the effectiveness of climate policies is hampered by significant challenges in data collection and analysis. The sheer complexity of the climate system, coupled with the diverse range of policy interventions, creates a formidable obstacle to establishing clear cause-and-effect relationships. Accurate measurement is crucial, yet obtaining reliable and comprehensive data across various sectors and geographical regions proves incredibly difficult.The difficulty in precisely measuring greenhouse gas emissions is a major hurdle.

Emissions inventories rely on a combination of direct measurements (e.g., from industrial smokestacks) and estimations based on activity data (e.g., fuel consumption, cement production). These estimations are often subject to significant uncertainties, especially in developing countries where data collection infrastructure may be limited or inconsistent. Furthermore, the global nature of the climate system means that emissions from one country can have impacts far beyond its borders, making it difficult to isolate the effect of individual national policies.

Attribution of Climate Change to Specific Policies

Attributing observed changes in climate patterns to specific policies is exceptionally complex. Climate change is a long-term process influenced by numerous natural and anthropogenic factors, making it challenging to isolate the impact of any single policy. Sophisticated statistical modeling and attribution studies are employed to attempt to disentangle these factors, but these methods often rely on assumptions and simplifications that introduce uncertainties.

For instance, even if a nation successfully reduces its own emissions, the global effect might be negligible if other nations increase their emissions. The inherent complexities of the climate system and the multitude of contributing factors make isolating the impact of any one policy extremely difficult.

Honestly, figuring out what actually works in climate policy is a nightmare! So many variables are at play, and it’s tough to isolate the impact of any single measure. This is especially true when you consider a country like China, which, as this article points out, mega polluter China believes it is a climate saviour , even while its emissions remain incredibly high.

That makes evaluating the effectiveness of their policies even more challenging – proving cause and effect is a huge hurdle in the fight against climate change.

Biases in Existing Datasets

Existing datasets used to evaluate climate policy effectiveness are not immune to biases. Data collection methods may vary significantly across countries, leading to inconsistencies and difficulties in making meaningful comparisons. For example, some nations may have more robust monitoring systems than others, leading to over- or under-representation of emissions in global inventories. Furthermore, reporting biases can occur, either intentionally or unintentionally, influencing the overall picture of policy effectiveness.

Data from developed nations might be more readily available and higher quality compared to developing countries, potentially leading to an inaccurate global assessment of policy impacts. This uneven distribution of data quality and quantity introduces bias into any global analysis of policy effectiveness.

Methods for Measuring the Impact of Climate Policies and Their Limitations

Before outlining different methods, it’s crucial to understand that no single method provides a perfect or unbiased assessment of climate policy effectiveness. Each approach has inherent limitations.

Figuring out what actually works in climate policy is a real headache; so many variables are at play! It’s like trying to predict election outcomes – and the Supreme Court hearing a case that could shift power from judges to state legislatures in election regulation, as seen in this article supreme court hears case that could empower state legislatures not judges to regulate elections , highlights the complexities of systemic change.

Similarly, with climate, disentangling the impact of individual policies from broader economic and environmental trends is incredibly difficult.

- Statistical Modeling: Sophisticated statistical models are used to estimate the relationship between policy interventions and changes in emissions or climate variables. However, these models are reliant on accurate data and often make simplifying assumptions that can limit their reliability.

- Process Evaluation: This approach focuses on assessing the implementation and effectiveness of policy mechanisms. It can reveal if policies are being implemented as intended, but it may not directly measure their impact on emissions or climate change.

- Impact Evaluation: This method attempts to quantify the actual effects of policies on emissions, climate variables, or other relevant outcomes. It requires robust data collection and sophisticated statistical techniques to control for confounding factors, but it is prone to uncertainties due to the complexity of the climate system.

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: This approach compares the costs of implementing a policy with the benefits it is expected to generate. However, accurately quantifying the benefits of climate change mitigation is challenging, given the long-term nature of the problem and the uncertainties involved.

The Role of Socioeconomic Factors

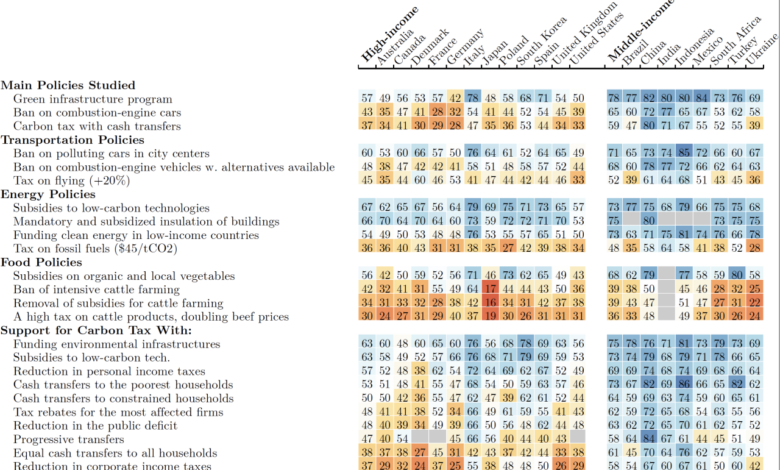

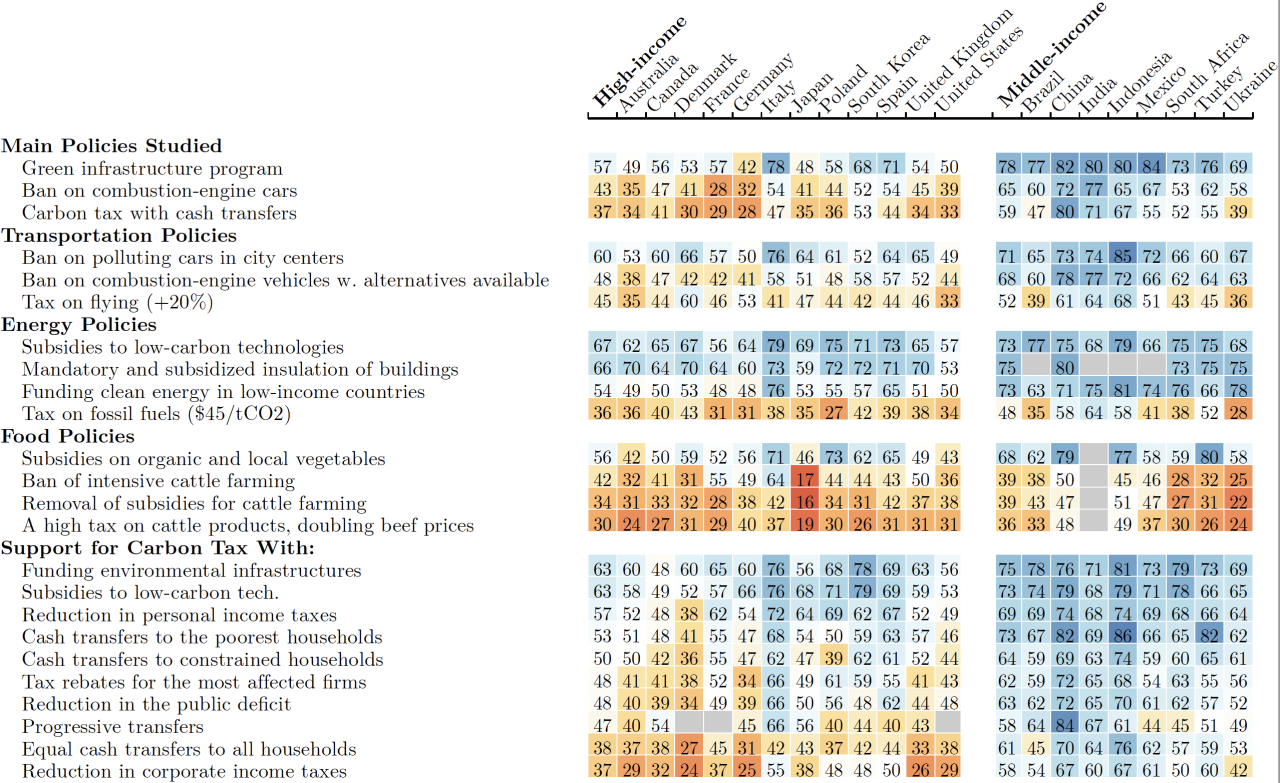

Climate policy effectiveness isn’t solely determined by the policy itself; it’s intricately woven with the social and economic fabric of the societies it aims to impact. Ignoring these socioeconomic factors leads to policies that are either ineffective or, worse, exacerbate existing inequalities and hinder sustainable development. Understanding this complex interplay is crucial for designing and implementing truly successful climate action.The success or failure of climate policies is significantly shaped by socioeconomic conditions.

For example, a carbon tax might be economically feasible and environmentally effective in a wealthy nation with robust infrastructure and a well-educated workforce capable of adapting to new technologies. However, the same policy implemented in a developing country grappling with widespread poverty and limited access to alternative energy sources could lead to disproportionate hardship for vulnerable populations, potentially fueling social unrest and ultimately undermining the policy’s goals.

Technological advancements, while offering solutions, also require investment and infrastructure which may be lacking in poorer regions, thus limiting their ability to participate in the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Poverty and Inequality’s Influence on Climate Policy Outcomes

Poverty significantly limits adaptive capacity to climate change impacts. Vulnerable populations often lack the resources to relocate, invest in climate-resilient infrastructure, or access early warning systems. Climate policies that don’t account for these disparities risk exacerbating existing inequalities, potentially leading to social unrest and undermining policy acceptance. For instance, a policy focused solely on carbon pricing without accompanying social safety nets could disproportionately impact low-income households who spend a larger portion of their income on energy.

Similarly, policies that prioritize large-scale renewable energy projects might displace communities, leading to further economic hardship and social injustice if adequate compensation and resettlement plans aren’t implemented.

Comparative Effectiveness of Climate Policies Across Socioeconomic Contexts

The effectiveness of various policy instruments differs drastically across socioeconomic contexts. Carbon taxes, while theoretically efficient in incentivizing emissions reductions, can be regressive in low-income settings where energy costs represent a larger share of household budgets. Subsidies for renewable energy technologies, while beneficial in promoting adoption, can be ineffective if the necessary infrastructure or technical expertise is lacking.

Regulations, such as building codes or vehicle emission standards, can be effective in wealthy countries with strong enforcement mechanisms but are often difficult to implement and enforce in countries with weak governance structures and limited resources. A case study comparing the success of carbon trading schemes in the European Union (a relatively wealthy and well-governed region) versus those in developing nations highlights this disparity, showing higher compliance and efficiency in the former.

Unintended Social and Economic Consequences of Climate Policies

Climate policies, even well-intentioned ones, can have unintended consequences. For example, policies promoting biofuels might lead to deforestation and biodiversity loss if not carefully managed. A rapid transition to electric vehicles could displace workers in the fossil fuel industry if adequate retraining and job creation programs aren’t implemented. Similarly, large-scale renewable energy projects, if not planned and implemented thoughtfully, could negatively impact local ecosystems and communities through habitat destruction or visual pollution.

These unintended consequences underscore the importance of conducting thorough social impact assessments and incorporating equity considerations into policy design.

Interaction Between Policy Instruments and Socioeconomic Factors, Why its so hard to tell which climate policies actually work

Different policy instruments interact differently with socioeconomic factors. Carbon taxes, for example, can be coupled with revenue recycling mechanisms to mitigate regressive impacts on low-income households. Subsidies for energy efficiency improvements can be targeted towards vulnerable populations to enhance their adaptive capacity. Regulations can be designed to be phased in gradually to allow for a smoother transition and minimize economic disruption.

A successful climate policy strategy requires a carefully designed mix of instruments tailored to the specific socioeconomic context and accompanied by robust social safety nets and supportive measures.

Political and Institutional Barriers

Evaluating the effectiveness of climate policies is significantly hampered by political and institutional factors that often overshadow the scientific and economic aspects. These barriers create a complex web of influences that make it difficult to isolate the impact of specific policies and determine their true success or failure. The interplay between political will, lobbying efforts, and institutional capacity profoundly shapes both the design and the evaluation of climate action.

Influence of Lobbying and Vested Interests

Powerful lobbying groups representing fossil fuel industries and other sectors with vested interests in the status quo frequently exert significant influence on climate policy. This influence can manifest in various ways, including direct lobbying of legislators, campaign contributions, and the dissemination of misinformation aimed at undermining public support for climate action. For example, the extensive lobbying efforts of the fossil fuel industry have, in many instances, resulted in the weakening or delay of climate regulations, making it harder to assess the potential benefits of stronger policies that were never implemented.

These actions create a biased environment where the evaluation of policies is skewed towards the interests of powerful lobbies, hindering objective assessments of effectiveness. The lack of transparency in these lobbying efforts further complicates the evaluation process.

Challenges in Coordinating Climate Policies Across Governmental Levels

Climate change is a global problem requiring coordinated action across various levels of government – local, national, and international. However, the fragmented nature of governance often leads to inconsistencies and inefficiencies in policy implementation. For instance, a national government might set ambitious emissions reduction targets, but the lack of supportive policies at the state or local level could hinder progress.

International cooperation, essential for addressing global climate change, faces similar challenges. Differing national interests, political priorities, and economic capacities often impede the formation of effective international agreements and their subsequent implementation. The Paris Agreement, while a landmark achievement, demonstrates the complexities involved in achieving global consensus and ensuring consistent action. The agreement’s success hinges on individual nations’ commitment, which varies significantly, making a comprehensive evaluation of its overall effectiveness challenging.

Institutional Weaknesses Hindering Effective Climate Policy Implementation and Monitoring

Effective climate policy implementation requires strong institutions capable of monitoring, enforcing, and adapting policies over time. However, many countries lack the necessary institutional capacity. This includes insufficient funding, inadequate staffing, limited technical expertise, and a lack of effective monitoring and evaluation frameworks. For example, the absence of robust monitoring systems can make it difficult to track emissions reductions, assess the effectiveness of specific policies, and identify areas needing improvement.

Weak enforcement mechanisms can allow polluters to circumvent regulations, undermining the intended impact of climate policies. The lack of consistent data collection and reporting standards further exacerbates these problems, making comparative analysis and evaluation across different jurisdictions extremely challenging.

Impact of Differing Political Priorities and Ideologies

The design and evaluation of climate policies are heavily influenced by prevailing political priorities and ideologies. Governments with a strong commitment to environmental protection tend to implement more ambitious climate policies and prioritize their evaluation. In contrast, governments prioritizing economic growth or energy independence may adopt less stringent measures, resulting in weaker climate action and potentially hindering the evaluation of even those modest efforts.

The political climate itself influences public perception and acceptance of climate policies, further complicating the evaluation process. For example, a policy perceived as economically burdensome or infringing on individual liberties might face strong political opposition, making its implementation and evaluation more challenging, regardless of its potential environmental benefits.

Long-Term Time Horizons and Uncertainties: Why Its So Hard To Tell Which Climate Policies Actually Work

Evaluating the effectiveness of climate policies presents a significant challenge due to the sheer length of time involved. Climate change unfolds over decades and centuries, making it difficult to definitively link specific policy interventions to observable outcomes within a reasonable timeframe for assessment. The long lag between policy implementation and measurable results makes it hard to disentangle the effects of a particular policy from other contributing factors, both natural and human-induced.The inherent uncertainties surrounding future climate scenarios further complicate the evaluation process.

Climate models, while constantly improving, still involve inherent uncertainties in projecting future temperature increases, sea-level rise, and extreme weather events. These uncertainties directly impact the ability to accurately predict the long-term effectiveness of different policy options. Different models produce varying results, making it difficult to establish a definitive baseline against which to measure policy success. For instance, a policy designed to reduce carbon emissions might be judged successful based on one model’s projections but deemed insufficient based on another’s.

Challenges in Evaluating Long-Term Policy Effectiveness

The extended timeframe required to observe the full impact of climate policies creates significant difficulties in evaluation. For example, policies aimed at reducing deforestation, while beneficial for carbon sequestration, may take decades to show significant effects on atmospheric CO2 levels. Similarly, policies promoting renewable energy sources, like large-scale solar or wind farms, require extensive infrastructure development and may only show substantial impacts on emissions after many years of operation.

These long lead times make it difficult to isolate the policy’s contribution from other factors affecting climate change, including natural climate variability and economic growth. Furthermore, societal and technological changes can render initial policy assumptions obsolete, complicating retrospective analysis.

Uncertainties in Future Climate Scenarios and Their Impact

The unpredictability of future climate scenarios significantly impacts policy evaluation. Variations in greenhouse gas emissions, the sensitivity of the climate system to these emissions, and the occurrence of unexpected climate tipping points all contribute to a wide range of potential future climate outcomes. These uncertainties make it difficult to accurately assess the effectiveness of policies designed to mitigate or adapt to climate change.

For example, a coastal protection policy designed to safeguard against a projected sea-level rise of one meter might prove inadequate if the actual rise exceeds that projection. Conversely, a policy that seems overly cautious based on one scenario might appear insufficient in another. This uncertainty necessitates a flexible, adaptive approach to policymaking, allowing for adjustments as new scientific evidence emerges and our understanding of the climate system improves.

Examples of Long-Term Climate Policies and Evaluation Difficulties

The Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, serves as an example of the difficulties in evaluating long-term climate policies. While the protocol aimed to limit emissions, assessing its overall effectiveness requires considering its implementation over multiple decades and comparing actual emissions with projected emissions under various scenarios. The Paris Agreement, while more recent, faces similar challenges in evaluating its long-term success, given the extended timeframe needed to observe the full impact of its commitments.

Policies focused on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies also present significant challenges. While CCS holds promise for mitigating emissions from fossil fuel power plants, the long-term effectiveness and safety of such technologies remain uncertain, requiring extensive monitoring and evaluation over extended periods.

Illustrative Representation of Long-Term Uncertainties

Imagine a graph with time on the x-axis spanning several decades and centuries. On the y-axis, plot projected changes in global average temperature under different climate scenarios (e.g., low, medium, and high emissions scenarios). Each scenario would be represented by a range of possible temperature increases, reflecting the uncertainties inherent in climate modeling. Overlay on this graph the projected impact of a specific climate policy (e.g., a carbon tax), showing a range of potential temperature reductions under each emissions scenario.

The graph would visually illustrate the wide range of possible future climate outcomes and how the effectiveness of the policy varies significantly depending on the actual emissions pathway and the climate system’s response. The overlapping uncertainty ranges would highlight the challenge of definitively attributing specific climate outcomes to the policy’s influence.

So, while definitively proving which climate policies are the most effective remains a monumental task, understanding the obstacles – the chaotic nature of the climate system, data limitations, socioeconomic disparities, and political hurdles – is the first step towards progress. It’s a journey of continuous learning, adaptation, and refinement, requiring collaboration across disciplines and a commitment to rigorous evaluation.

The stakes are high, but the quest for effective climate solutions is a journey worth pursuing with open eyes and a pragmatic approach.