Americans Are Wrong to Wish for Stable Bipartisanship

Americans Are Wrong to Wish for an era of stable bipartisanship. That seemingly idyllic vision of harmonious political cooperation, where both sides readily compromise, is actually a dangerous illusion. This isn’t about wishing for more fighting – it’s about recognizing that the pursuit of unwavering bipartisanship often stifles necessary progress and masks deeper, more damaging issues. We’ll explore why the myth of “the good old days” of bipartisan harmony is precisely that – a myth – and delve into the crucial role of robust political debate in a truly healthy democracy.

Throughout history, periods perceived as bipartisan often hid significant underlying tensions and compromises that ultimately failed to address fundamental problems. We’ll examine specific policy examples, dissecting their long-term consequences and contrasting the rhetoric of unity with the actual legislative outcomes. By understanding the pitfalls of forced consensus, we can begin to appreciate the value of constructive disagreement and the importance of fostering a political landscape that embraces robust debate, even when it’s uncomfortable.

The Illusion of Stable Bipartisanship

The yearning for a perpetually harmonious, bipartisan America is a powerful, almost mythical, desire. However, a closer look at American history reveals that periods of perceived bipartisanship are often more accurately described as uneasy truces or strategic alliances forged amidst underlying ideological chasms. These moments of apparent unity frequently mask deeper divisions and compromises that, while seemingly successful in the short term, often lead to unforeseen and sometimes detrimental long-term consequences.The notion of consistent bipartisan cooperation significantly underestimates the fundamental differences in American political philosophy.

The very structure of the two-party system, with its inherent competition for power, creates a dynamic that often prioritizes political maneuvering over genuine consensus-building. Furthermore, the ever-shifting social and economic landscapes of the nation continuously reshape the political priorities of both parties, making long-term bipartisan agreements challenging to maintain.

Examples of Perceived Bipartisanship and Their Outcomes

Several historical periods are frequently cited as examples of bipartisan success. The post-World War II era, for instance, witnessed significant cooperation between Republicans and Democrats on issues such as the Marshall Plan and the GI Bill. While the Marshall Plan is lauded as a triumph of international cooperation and a key factor in containing the spread of communism, its long-term consequences included the bolstering of anti-communist regimes, some of which were later criticized for human rights abuses.

Seriously, folks, longing for stable bipartisanship in America is naive. We need robust debate, not cozy consensus. The recent arrest of an election software CEO, election software ceo arrested over data theft storing data on servers in china , highlights the critical need for transparency and oversight – things often lost in the pursuit of bipartisan harmony.

Blind faith in a unified front risks ignoring crucial issues like this, proving that healthy conflict is vital for a functioning democracy.

Similarly, the GI Bill, while undeniably beneficial to many veterans, also contributed to a surge in suburban development, exacerbating existing inequalities in housing and access to resources. The apparent harmony of this era, therefore, masked complex geopolitical and socioeconomic trade-offs.

The Rhetoric of Bipartisanship versus Legislative Outcomes

The rhetoric surrounding bipartisanship often presents a stark contrast to the actual legislative outcomes. Politicians frequently employ bipartisan language to frame their policies as universally beneficial and garner broader public support. However, the compromises made in the name of bipartisanship often lead to diluted or ineffective legislation that fails to adequately address the core issues at hand. For example, budget negotiations frequently result in incremental changes rather than bold, transformative action, reflecting a compromise that often satisfies neither party’s core constituents.

The resulting legislation, while presented as a bipartisan achievement, might ultimately fail to achieve its stated goals due to these compromises. This creates a cycle where the appearance of bipartisanship is prioritized over meaningful policy change.

The Great Society Programs: A Case Study

The Great Society programs of the 1960s, while championed as a bipartisan effort to address poverty and inequality, also faced significant opposition and ultimately yielded mixed results. While some programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid, had lasting positive impacts, others faced criticism for their inefficiency and unintended consequences. The rhetoric of a unified nation working towards a common goal masked the underlying tensions and disagreements regarding the scale and scope of government intervention.

The debate surrounding these programs continues to shape political discourse today, highlighting the complexities and lasting impacts of even seemingly successful bipartisan initiatives.

The Dangers of Apolitical Stagnation

The pursuit of bipartisanship, while often lauded as a desirable goal, can paradoxically lead to a dangerous form of political stagnation. A relentless focus on compromise and consensus, without regard for the urgency of pressing issues, can result in inaction and ultimately, harm society. The desire for a perfectly balanced, agreeable solution can overshadow the need for effective, even if controversial, policy changes.

This can create a situation where the perfect becomes the enemy of the good.The allure of bipartisanship can mask the reality of deeply entrenched ideological differences. In an attempt to appease all sides, the resulting policies might be diluted to the point of ineffectiveness, failing to address the root causes of problems and offering only superficial solutions. This leaves many crucial issues unresolved, leading to a build-up of frustration and potentially exacerbating the very problems the system was designed to fix.

Historical Examples of Inaction Due to Prioritizing Bipartisanship

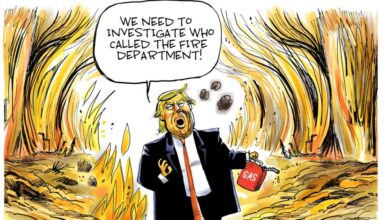

The consequences of prioritizing bipartisanship over decisive action are visible throughout history. Consider the slow response to the growing environmental crisis. While there’s been a broad scientific consensus on the reality and severity of climate change for decades, political gridlock, fueled by a desire for bipartisan agreement, has hampered the implementation of effective policies. The result is a delayed and inadequate response, increasing the severity of the climate crisis and its impact on future generations.

Similarly, the slow and often ineffective response to the opioid crisis can also be attributed to a failure to prioritize decisive action over the pursuit of bipartisan consensus. The lack of swift and comprehensive solutions has resulted in widespread suffering and loss of life.

Honestly, yearning for consistent bipartisan harmony in America feels naive. The recent Supreme Court decision, and its implications, perfectly illustrate this. Check out this insightful article on what is the effect of the supreme courts affirmative action ban to see how deeply divisive even seemingly straightforward issues can be. The fallout shows us that “stable bipartisanship” often masks a lack of meaningful progress on critical social issues, and maybe that’s not such a bad thing.

The Stifling Effect of Bipartisanship on Innovation and Bold Solutions, Americans are wrong to wish for an era of stable bipartisanship

The desire for bipartisanship can stifle innovation and the implementation of bold, transformative solutions. When the primary goal is to find common ground, radical ideas that might offer a path to progress are often dismissed as too divisive or impractical. This self-imposed limitation prevents the exploration of creative and potentially effective solutions that lie outside the realm of conventional political thought.

The pursuit of a comfortable, bipartisan consensus can thus inadvertently limit the scope of possible solutions and ultimately hinder progress. For example, the relatively slow adoption of universal healthcare in the United States, compared to many other developed nations, can be partly attributed to the challenges of achieving bipartisan support for such a significant policy change. The desire for compromise has resulted in a patchwork system that is often less efficient and equitable than more comprehensive, single-payer models.

Many Americans long for the “good old days” of stable bipartisanship, but that’s a nostalgic fantasy. Healthy debate, even fierce disagreement, is vital. Consider this: the recent news that a top Democrat senator agrees with Trump on the TikTok issue, as reported in trump was right on tiktok says top democrat senator , highlights how partisan gridlock isn’t always bad; sometimes it forces a necessary re-evaluation of entrenched positions.

Ultimately, a little friction can lead to better, more considered policies.

The Role of Ideological Polarization

The yearning for a return to the halcyon days of stable bipartisanship in American politics often overlooks the profound shift in the ideological landscape. Understanding this polarization is crucial to comprehending the challenges facing our current political system and the difficulties in achieving meaningful compromise. The increasing divergence of beliefs and values between the Republican and Democratic parties isn’t simply a matter of policy disagreements; it represents a deeper chasm in fundamental worldviews.Increased ideological polarization in American politics is a complex phenomenon with multiple contributing factors.

These factors intertwine and reinforce each other, creating a feedback loop that makes compromise increasingly difficult. The rise of partisan media, gerrymandering, and the increasing influence of money in politics are just a few of the key elements driving this trend.

Factors Contributing to Ideological Polarization

The following table Artikels several key factors contributing to increased ideological polarization, their impact on bipartisanship, and potential solutions.

| Factor | Description | Impact on Bipartisanship | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partisan Media | The proliferation of news sources catering specifically to either the left or right wing, often presenting biased or one-sided information, reinforcing pre-existing beliefs and creating echo chambers. | Reduces exposure to opposing viewpoints, making compromise seem unnecessary or even treacherous to one’s “tribe.” Encourages animosity and distrust towards the opposing party. | Promoting media literacy, supporting fact-checking initiatives, and encouraging consumption of diverse news sources. Regulation of overtly biased reporting could also be considered, though this is a complex issue with First Amendment implications. |

| Gerrymandering | The manipulation of electoral district boundaries to favor one party over another, resulting in safe seats for incumbents and a lack of competitive elections. | Reduces the incentive for politicians to appeal to a broader electorate, leading to more extreme positions and less willingness to compromise. Reinforces partisan divides by creating districts overwhelmingly dominated by one party. | Independent redistricting commissions, court challenges to gerrymandered districts, and the adoption of alternative electoral systems (e.g., ranked-choice voting) to reduce the power of gerrymandering. |

| Increased Political Polarization | The growing ideological distance between the Republican and Democratic parties, reflected in increasingly divergent policy positions and rhetoric. This is fueled by social and cultural divisions as well as economic anxieties. | Makes finding common ground extremely challenging, as even seemingly minor compromises can be framed as betrayals of core principles. Leads to gridlock and an inability to address pressing national issues. | Promoting civil discourse and respectful dialogue, focusing on areas of common ground, and encouraging bipartisan collaboration on specific policy issues. Investing in civic education to foster a better understanding of political processes. |

| Influence of Money in Politics | The significant role of campaign donations, lobbying, and Super PACs in shaping political agendas and influencing policy decisions. This allows wealthy donors and special interests to exert disproportionate influence. | Creates an environment where politicians are more responsive to the needs of wealthy donors than to the needs of the general public, leading to policies that exacerbate inequality and further divide the population. | Campaign finance reform, increased transparency in lobbying activities, and stricter regulations on Super PACs to limit the influence of money in politics. Public financing of elections could also be considered. |

Party Strategies and Compromise

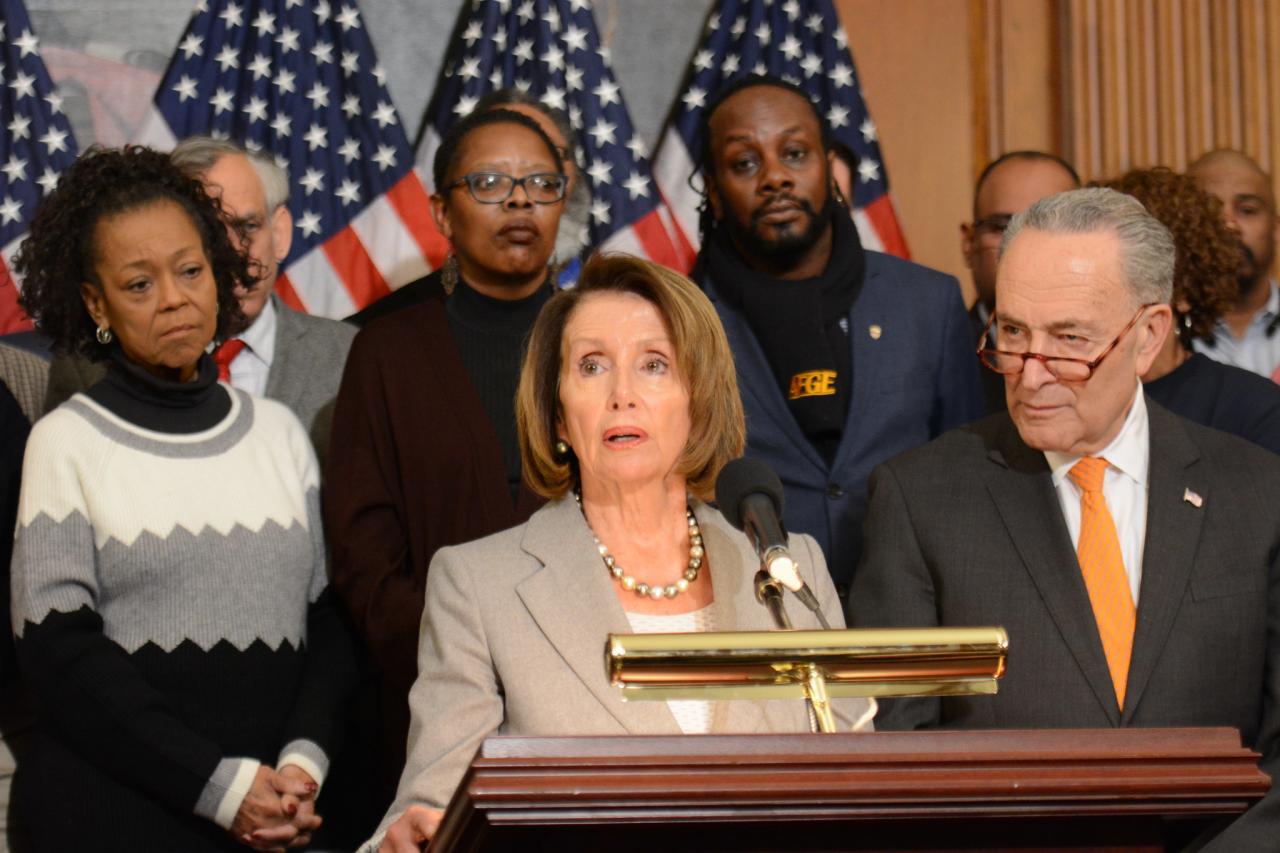

The strategies employed by the Republican and Democratic parties to appeal to their respective bases often exacerbate the challenges of compromise. Republicans increasingly rely on appeals to cultural conservatism, religious values, and economic libertarianism, while Democrats emphasize social justice, environmental protection, and economic equality. These appeals, while effective in mobilizing their respective bases, often serve to deepen the divisions between the parties, making it harder to find common ground on even seemingly non-controversial issues.

The rhetoric employed by both parties frequently frames the other as an existential threat, making compromise seem like a betrayal of one’s principles. This strategy, while effective in energizing the base, makes bipartisan cooperation extremely difficult. The focus on appealing to the extremes within each party’s base often overshadows the need for moderate solutions that could garner broader support.

The Importance of Political Debate and Disagreement: Americans Are Wrong To Wish For An Era Of Stable Bipartisanship

A vibrant democracy isn’t defined by unanimous agreement; it thrives on the clash of ideas. The ability to engage in robust, even contentious, political debate is not a flaw, but a fundamental strength. It’s through this process of disagreement and deliberation that we refine policy, expose flaws in reasoning, and ultimately arrive at solutions that better reflect the needs and values of the populace.

Suppressing dissent, in contrast, fosters stagnation and allows harmful policies to persist unchecked.Robust political debate, while sometimes uncomfortable, serves as a vital check on power. It ensures that proposed legislation is thoroughly vetted, that potential consequences are carefully considered, and that the voices of all stakeholders are heard. The free exchange of ideas forces politicians to articulate their positions clearly, defend them rigorously, and ultimately, be accountable to the electorate.

Without this dynamic interplay of opposing viewpoints, the risk of tyranny of the majority or the unchecked influence of special interests significantly increases.

A Constructive Political Debate: Infrastructure Investment

Imagine a scenario where the government is considering a significant investment in national infrastructure. One political party, let’s call them the “Pragmatists,” advocates for a large-scale, government-led program focusing on high-speed rail and renewable energy projects. They argue this will create jobs, boost economic growth, and address climate change. Their proposed funding mechanism involves a combination of increased corporate taxes and a modest increase in the national sales tax.

They present detailed economic models projecting job creation and long-term cost savings.The opposing party, the “Fiscal Conservatives,” counter with a proposal for smaller-scale, targeted infrastructure improvements focused on repairing existing roads and bridges. They argue that the Pragmatists’ plan is too expensive, risks wasteful spending, and places an undue burden on businesses. They propose a plan funded primarily through existing infrastructure budgets, prioritizing projects with the highest return on investment.

They present their own economic analysis highlighting the potential for cost overruns and inefficient allocation of resources in the Pragmatists’ plan.After weeks of intense debate, public forums, and expert testimony, a compromise is reached. The final plan includes investments in both high-speed rail in densely populated corridors and crucial repairs to existing infrastructure nationwide. Funding is secured through a combination of increased corporate taxes on the most profitable companies, reallocation of existing budget items, and a small increase in fuel taxes dedicated solely to infrastructure projects.

This compromise acknowledges the economic benefits of long-term investments while addressing concerns about fiscal responsibility. The debate highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, leading to a more comprehensive and balanced outcome.

A Framework for Productive Political Discourse

Productive political discourse requires a commitment to several key principles. First, participants must actively listen to opposing viewpoints, seeking to understand the underlying reasons and values motivating those positions, rather than simply dismissing them. Second, arguments should be grounded in facts and evidence, avoiding emotional appeals or personal attacks. Third, a willingness to compromise and find common ground is essential, even if it means sacrificing some aspects of one’s ideal position.

Finally, a commitment to civil and respectful engagement, even in the face of strong disagreement, is crucial for maintaining a healthy and productive political environment. This framework acknowledges that meaningful progress often requires acknowledging the validity of some opposing arguments and finding solutions that incorporate elements from different perspectives.

The Myth of “The Good Old Days”

The yearning for a past era of harmonious bipartisanship in American politics is a common sentiment, often fueled by a romanticized view of history. However, this nostalgic perspective overlooks the persistent and often intense political divisions that have characterized the nation throughout its existence. The reality is far more complex than a simple dichotomy of “good old days” versus present-day dysfunction.The notion that past eras were inherently more bipartisan is a significant misconception.

While periods of apparent cooperation might exist, a closer examination reveals deep-seated ideological conflicts and bitter partisan battles that often mirrored, and sometimes exceeded, the intensity of contemporary political disagreements. Focusing solely on instances of collaboration while ignoring the extensive periods of conflict creates a distorted picture of the past.

Examples of Historical Political Conflict

The myth of a consistently bipartisan past is easily debunked by examining key moments in American history. The debates surrounding the ratification of the Constitution, for instance, were fierce and deeply divisive, splitting the nation into Federalist and Anti-Federalist camps. The Civil War, arguably the nation’s most profound political conflict, stemmed from irreconcilable differences over slavery and states’ rights, leaving a legacy of division that continues to resonate today.

The Progressive Era saw intense clashes between reformers and entrenched interests, while the Cold War era witnessed significant domestic political battles over foreign policy and the threat of communism. Even seemingly less turbulent periods, such as the post-World War II economic boom, were punctuated by significant disagreements over civil rights, social welfare programs, and the Vietnam War. These historical examples highlight the enduring presence of political conflict, undermining the idea of a consistently harmonious past.

Selective Interpretation of Historical Narratives

The selective use of historical narratives often contributes to the myth of a more bipartisan past. For example, accounts of the “Great Society” era under President Lyndon B. Johnson might emphasize the passage of landmark legislation like Medicare and Medicaid, portraying a spirit of cooperation between Democrats and Republicans. However, these accounts often downplay the significant opposition to these programs from conservative elements within both parties and the intense political battles surrounding their enactment.

Similarly, accounts of presidential administrations might highlight instances of bipartisan compromise while neglecting the substantial opposition and partisan maneuvering that frequently accompanied them. This selective emphasis on collaboration serves to support particular political agendas, either by promoting a sense of nostalgia for a perceived golden age or by using the past to criticize the present.

The Construction of a False Narrative

The persistent myth of a more harmonious past serves various political purposes. For some, it fuels a longing for a return to a simpler time, often perceived as less polarized and more civil. For others, it provides a benchmark against which to measure the current political climate, often leading to a sense of disillusionment and pessimism. This narrative, while emotionally resonant, is ultimately a misleading simplification of a complex historical reality.

By acknowledging the persistent presence of political conflict throughout American history, we can foster a more realistic understanding of the challenges of building consensus and achieving meaningful political progress.

The desire for stable bipartisanship, while seemingly noble, can be a dangerous trap. It risks stagnation, preventing the bold solutions needed to tackle pressing societal challenges. Instead of clinging to a romanticized past, we should embrace the power of productive political debate, even amidst ideological polarization. A healthy democracy thrives on the clash of ideas, allowing for the evolution of policy and the implementation of effective solutions.

The path forward isn’t about eliminating disagreement, but about channeling it constructively to achieve meaningful progress.